Two Notable WWII Veterans Now at Rest at Miramar National Cemetery

Fought in Key Battles in the Pacific and in Europe

(Sept. 27, 2021) Two World War II veterans with remarkable backgrounds—a Marine officer who fought on Iwo Jima, and an Army officer with an historic ancestor—were buried in September at Miramar National Cemetery, and now lie at rest among their fellow veterans.

Retired Marine Colonel Dave E. Severance, 102, was buried at Miramar on Sept. 15. As a young captain, he was in command of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment on Feb. 23, 1945, when he ordered five of his Marines and a Navy Pharmacist’s Mate to raise an American flag atop Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima. The famous photograph of the flag-raising inspired the Marine Corps statue in Washington, D.C.

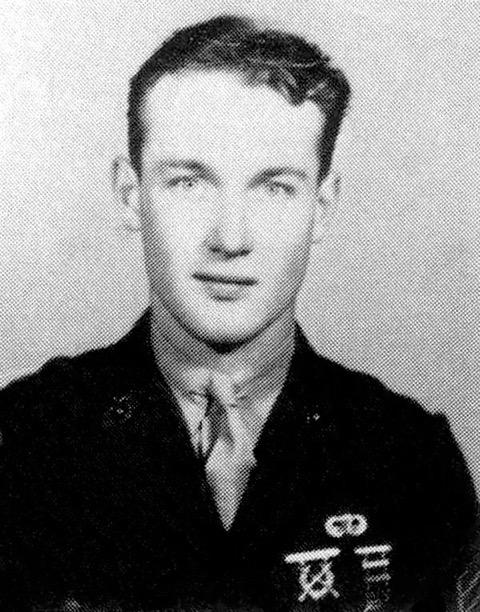

Former Army Lt. George E. Key, 96, was buried at Miramar on Sept. 24. Key landed on the beaches of Normandy with a combat engineering regiment on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and later fought in the bloody, bitter-cold Battle of the Bulge. Following World War II, he was recalled for service during the Korean War. Key is the great, great grandson of Francis Scott Key, who wrote the lyrics to “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Severance led Marines on Iwo JIma

In an August 2021 interview with Coffee or Die Magazine, Severance described his World War II experiences. He enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1938 and attended recruit training in San Diego. He completed airborne training, and in 1942, the young, college-educated sergeant was commissioned a second lieutenant.

In 1943, Lt. Severance deployed to the Pacific theater with the Paramarines and saw combat for the first time in the jungles of Bougainville. He proved himself in combat, leading his cutoff platoon out of a Japanese ambush with minimal casualties.

In April 1944, Severance was promoted to captain, and given command of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment. On Feb. 19, 1945, Severance and the men of Company E landed on the black sand beaches of Iwo Jima, having no idea of the impact their actions on that strategic island would have on Americans and the future Marine Corps.

At 10:20 a.m. on Feb. 23, 1945, one of Severance’s platoons reached the summit of Mount Suribachi and raised a small American flag.

‘Troops yelling and cheering’

“All the ships at sea started their sirens going, and troops were yelling and cheering,” Severance told San Diego’s NBC 7 during a 2015 interview. “You definitely could see that it is an American flag.”

Company E fought at Iwo Jima for 36 days, and 80 percent of Severance’s men were either killed or wounded in action there.

The Marine Corps War Memorial was dedicated near Arlington, Virginia, on the Marine Corps’ birthday in 1955. In June 1996, Severance carried the Olympic torch from Arlington National Cemetery to the steps of the Marine Corps War Memorial.

Severance retired from the Marine Corps in 1968 while serving as assistant director of personnel, headquarters, Marine Corps. The old Marine died Aug. 2, 2021, at his home in La Jolla. He was 102.

George Key landed in Normandy on D-Day

George Key was carrying a combat pack, hand grenades, two bandoliers of ammunition, a gas mask and his M-1 rifle when he stumbled ashore in the face of deadly enemy fire on D-Day, June 6, 1944, on a Normandy beach. He was wet to the bone from the waves that had almost drowned him.

A combat engineer, Key was in the first wave of soldiers and “struggled to find a foothold against the German position dug in heavily-fortified concrete bunkers above them,” according to a profile in the book WWII Heroes: 100 Portraits and Biographies of WWII Veterans.

As U.S. forces pushed the Germans into retreat across France, Key’s platoon encountered scattered German resistance from snipers, hidden machine gun nests, and enemy soldiers lurking in dug-in positions.

As platoon commander, Key told interviewers, “It’s a hard thing to do to send a guy on a patrol when you don’t know if he’s going to come back or not…but you have to send somebody. It weighs on your conscience.”

Key’s men fought on against German occupation forces in Belgium, pushing the enemy toward the German border. The combat engineers often had to rebuild bridges destroyed by the retreating army, or install temporary causeways across rivers to safely move U.S. troops.

Key’s engineers held the line

When a desperate German blitz on Dec. 16, 1944, developed into the Battle of the Bulge and pushed Allied forces back, Key’s engineers held the line at a bridge crossing, according to the book, linking up there with other U.S. units. Months later, Germany surrendered.

Following WWII, and after a stint of service in Japan during the Korean War, Key’s patriotic efforts turned to honoring the American flag. As the great, great grandson of Francis Scott Key of “The Star-Spangle Banner” fame, he honored his ancestor’s memory by organizing a local fundraising project to help the Smithsonian Institution restore a giant 15-star American flag that had flown over Baltimore’s Fort McHenry during the War of 1812.

As the British Navy bombarded Fort McHenry on the night of Sept. 13-14, 1814, Francis Scott Key watched from a neutral ship anchored in the Chesapeake Bay. At dawn, he could see that the huge American flag raised by the defenders still flew over the embattled fort. In 1931, Congress declared “The Star-Spangled Banner” to be America’s national anthem.

George Key also co-founded a program aimed at retiring damaged flags with dignity, and another program inviting spouses of deceased veterans to honor their loved one by flying the veteran’s casket flag over City Hall. He also gave talks at schools and civic organizations about the history of the American flag and the “The Star-Spangled Banner”.

Key was born in 1924 in the U.S. Panama Canal Zone while his father was a government employee there. A fervent patriot, his father named Key’s brothers Francis Scott Key and Patrick Henry Key. Eventually, the family moved to California, where Key attended high school in Glendale. After a year of community college, he enlisted in the Army in 1943 to train as a combat engineer.

Following the Korean War, Key was employed by the Glendale Department of Water and Power. After retirement, he relocated to San Clemente where he died peacefully in his sleep on Dec. 31, 2020. He was 96.

By Bill Heard, PIO

# # #